Writer and educator Peter Markus is the author of six books of fiction, one book of nonfiction, and one book of poetry. To read his work is to take a boat through a muddy river of repetition and obsession and empathy and imagination and kindness and loss. Each book feels like an ambient, ongoing search for peace and ease. As minimal as a fable, as rhythmic as a lullaby.

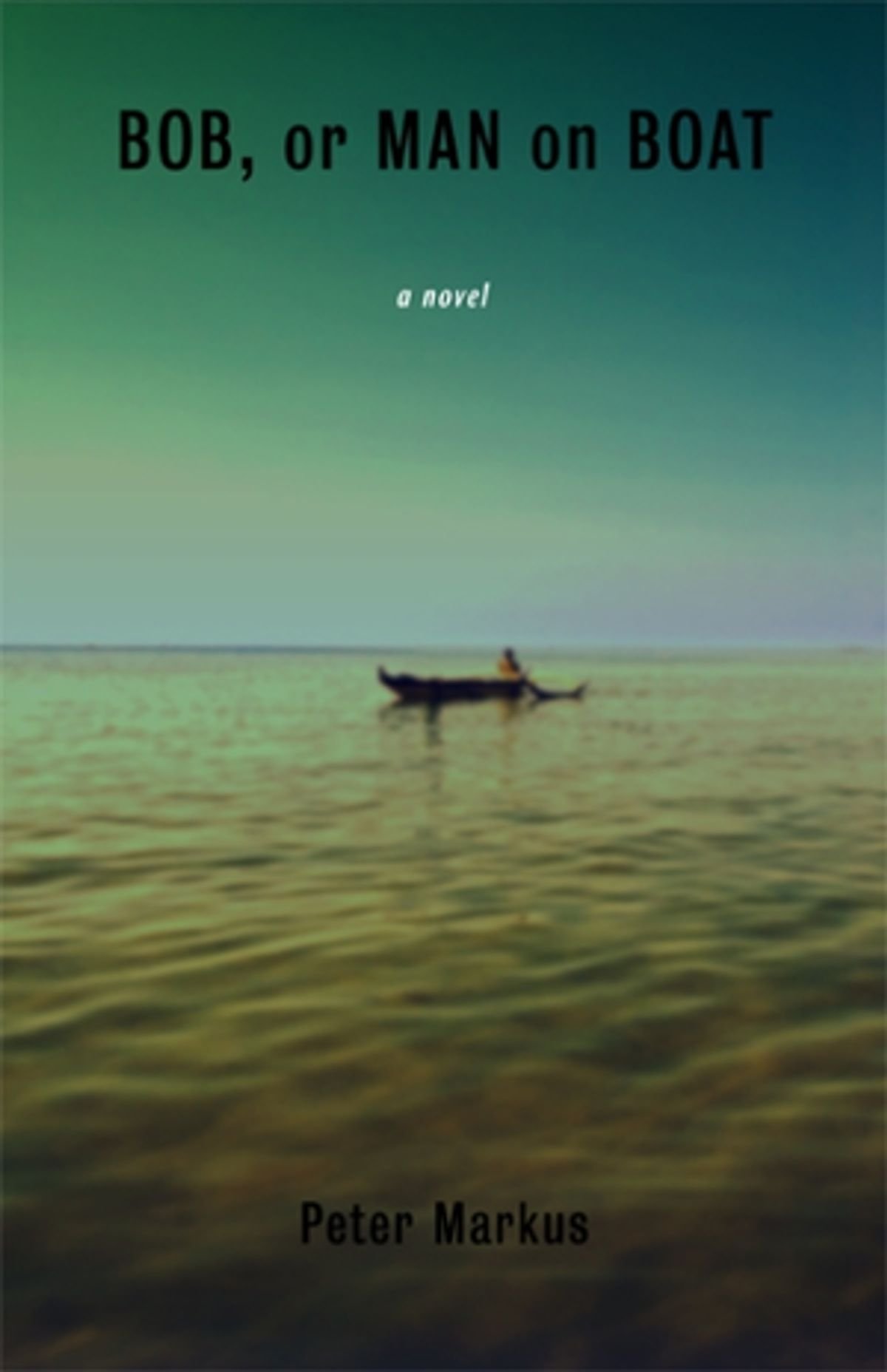

After reading Markus’ debut novel, Bob, or Man on Boat (Dzanc Books, 2008), I read his debut poetry collection, When Our Fathers Return to Us As Birds (Wayne State University Press, 2021) and I am now reading his short story collection, The Fish and the Not Fish (Dzanc Books, 2014), where every single word in the book is one syllable. How’s that for a constraint?

While Markus started publishing his fiction 20 years ago, it wasn’t until last year that he released his first poems. Written in response to the growing illness and ultimate passing of his father, each page still manages to maintain a tender shine. A brightness, a hopefulness, a love found so prominently throughout all of his work. I spoke with the author and educator about his writing, his obsessions, his river, his favorite music, and much more.

Let's start with an icebreaker: When was the last time you went fishing? Or, alternatively, since it's winter, do you ice fish?

Yes, let's begin with what's really important here. I'm fishing even when I'm not fishing. The same might be said for writing: I'm writing even when I'm not. I go down to the river often. Sometimes it's to cast a lure. Oftentimes it's just to stand, to be close to the water. In the winter walking out onto the water, onto the ice; it's a thrill to be out above it. Ice is just now beginning to form on the river as I write this. It's been a warm winter this winter, the river is late to ice. Global warming, the winter gods being punished, etc. It's not like when I was a kid, for sure. I miss those winters. The river isn't the same river either. It's better now. More kinds of fish to fish. When was the last time? was the question. Early spring is when the walleye run hard on the river, though I also like to spear pike through the ice, whenever I can, which isn't often enough.

Your writing is often a practice in repetition and constraint/restraint. Can you talk a bit about obsession and sequencing and how it's similar and/or different throughout your writing projects?

Repetition is a form of ritual. If I say the same words often enough, the words become a kind of prayer, a mantra, a conjuring, an incantation. This is how worlds get made, how stories get told, how poems take shape, how ghosts are called forth, one right word after the other. To find those words made of fire, of steel, of mud, of water, and to see what might be said through them.

I don't know how any writer can write without being in touch with one's own obsessions. Our obsessions make us who we are. What possesses you, what haunts you, what holds you to the world as you know it? These are the kinds of questions the writer needs to be asking. Not, Is this story or plotline plausible? Not, Is this character fully realized? But that's where most stories are bound by and therefore limited by such frivolous questions. Here are the questions I think writers should be asking: What words can you not live without? Where is the world most alive in you through the dialect of the human heart? If you were to make a pencil into a guitar, which words would make up this new instrument's six strings? Mud, fish, river, brother. Bird, father, sky, tree, house, etc. What words do you love: the sound of, the look of, the feel of? What better place to begin but there? Of course, I can only speak to what works for me, which might also point to where my own shortcomings reside. But I don't know how to be anyone but who I am, as a man, as a writer, as a father and son and brother and husband. I'm all wrapped up in those handful of particulars. If we're not obsessed by who we are and how we place ourselves within the world, who else will be?

Know this too: that I often forget what I say once I say it. I am always having to look back and to make from what has come before. That's all I might say about the issue of the sequence. The only sequence I can ever keep in front of me is the sequence that is made to be a sentence. As for restraint, constraint, restriction, all of which are nothing more than devices to stimulate and liberate the imagination, those are always present in my wheelhouse. My chosen viewfinder is limited by the few things I think I know. I prefer the keyhole to the door I suppose is what I am trying to say.

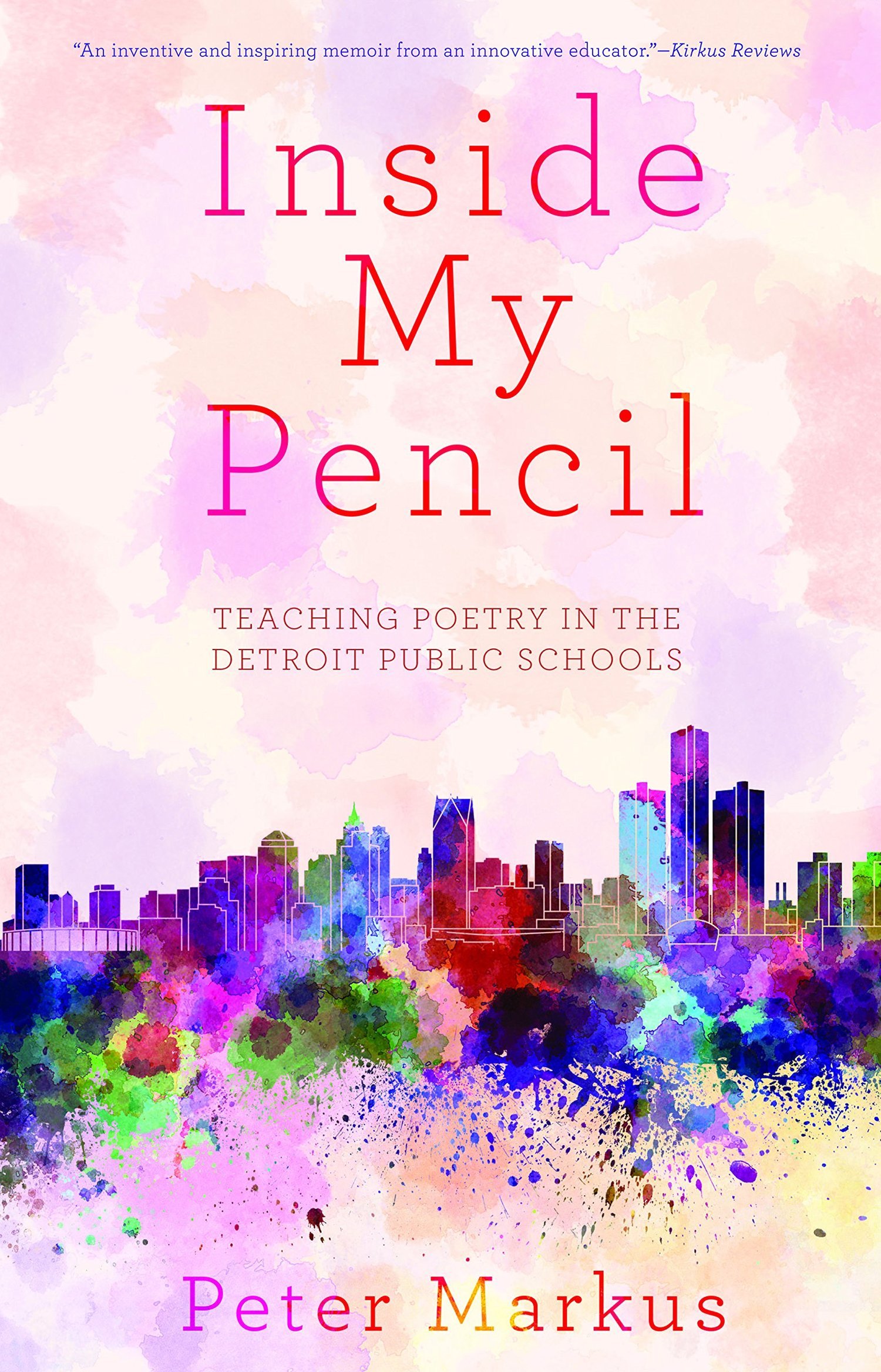

Your debut poetry collection, When Our Fathers Return to Us as Birds, is very much a book-length meditation on illness and family and loss, while many debut collections can often be the 'best of' from a poet. What initially brought you to poetry and why did you feel it was necessary to use this style of writing for this part of your life?

What brought me to poetry and lured me away from fiction was the truth and the desire to tell the truth in a new way. I was tired of lying, tired of making things up. I knew I had to write poems about my father and the particulars about him getting sick and dying when what I really wanted to do was to look away. Poetry gave me the courage to look closer, to pay attention, to be present when my heart, at its weakest, at its most paltry and impoverished, wanted to turn away.

Have other poetry collections of yours been assembled in the past and left on the drawing board?

My books of fiction have been called by others books of poems, though I suppose that might be due to my attention to language first and foremost and also my failings to tell a story straight or in conventional ways (which never interested me). I never thought of myself as a poet until my father got sick and I took to heart the words of Raymond Carver who said "Make use. Put it all in." I was in no mood or shape to tell more lies or to make a fiction of what I was seeing since what I was seeing could only be seen the way that I was seeing it. To see or to say about it in any other way wasn't an option.

Have you found yourself writing poems since releasing this project?

I am still writing poems, yes, since the act of writing poems changed the way I align with the world and made me see the poems that are still out there in the world for me to try to take hold of. What Jim Harrison says I think is true: that birds are poems we haven't yet caught. And maybe the inverse might also be true: that poems are birds and on my daily walks along the river and in the woods with my dog I am hoping to flush out the thing—the poem-as-bird—that I haven't yet said or seen.

In other words, what are you currently working on?

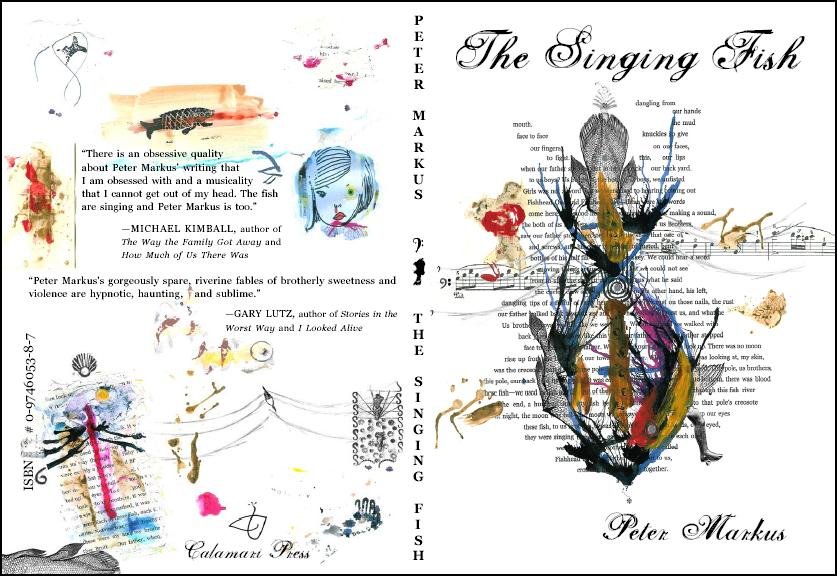

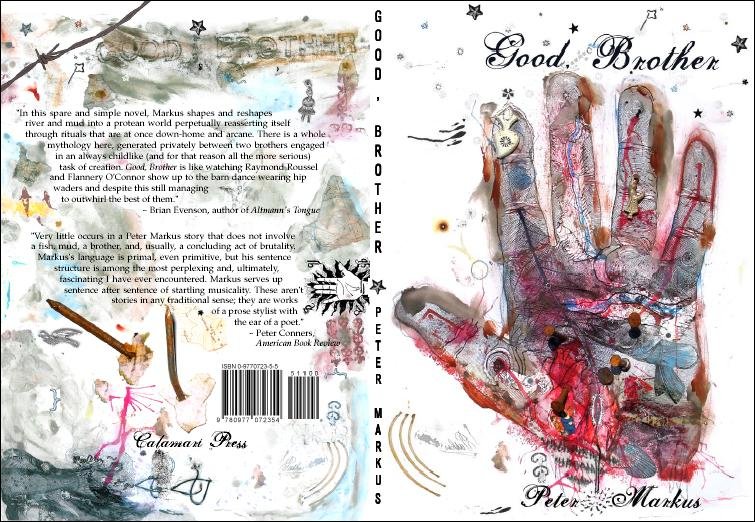

As it was, when I was writing the stories that make up the collections Good, Brother, The Singing Fish, and We Make Mud, once I find my subject, once I locate the words behind the subject, I can't turn the water off. There is no knob on the faucet to stop it from coming. I'm not complaining. As you mentioned earlier, obsession is what drives the writing. So yes, I am writing more poems about more of the same things: the river, birds, fish, my father, or in other words the world as I have come to know it.

I remember in a past interview where you said you were working on a novel where every word is only one syllable. I found an example of this in your short story "Death in the Woods". Is this still something you're tinkering with? The idea sounds so daunting and yet so intriguing as well.

I wrote a book made up entirely of monosyllabic words that Dzanc published in 2014 called The Fish and the Not Fish. It's a collection of three longish fictions punctuated by three shorter pieces. I wanted to see if I could write an entire novel under or using the same constraint. The piece you mention is a part of that manuscript, In a House in a Woods, though I've since lost interest in ever publishing it. I’m a fan of throwing some fish back.

Outside of your own art and writing, what albums/artists/plays/films have captivated you in recent months?

Let me stick with music, since I'm a failed musician and making music and my inability to do so or at least stick with it is one of my few regrets. I go for months at a time where I only listen to Elliott Smith. When I was a kid it was The Rolling Stones. I once spent three straight days listening to nothing but “Venus in Furs” on constant repeat and I think I’m a better man and better listener because of it. Bill Callahan is someone I never grow tired of. Someone once called me the Bill Callahan of the literary world and I can't say anything said of me has ever made me happier. A close second was when a student once said I was the Snoop Dogg of the lit world, though that, honestly, was a bit of a stretch. It’s hard to pick and choose, to not indulge in the act of making a list. I’ll resist the temptation to do so, though I will say this: that I think Jeff Buckley was his own kind of singer with his own kind of song. I want to write in such a way so that someone might say something along the lines of that: that Peter Markus was his own kind of singer, his own kind of song.

If you can, provide a photo of your workspace (or describe with words). What are some essentials (coffee, wine, cigarette, noises) while you create?

I like to sit in the dark when I write. I just recently stopped drinking coffee. I rarely drink. Don't smoke. If this sounds like a Minor Threat song, so be it. But I don't ever listen to music when I sit down to write. I like the quiet. The act of writing always begins with the act of picking up a book. I have vivid memories of watching my hundred-year-old grandfather sitting by the window in the house that he died in reading The Bible with a magnifying glass in his hand, the sunlight making a halo around his head of thick white hair. I tend to a different kind of gospel, I suppose. The gospel according to Jack Gilbert, Jim Harrison, Linda Gregg. When I read, I keep reading until I find that I have something that needs to be said back. That’s when I pick up the pen.

For this ongoing author interview series, I'm asking for everyone to present a writing prompt. It can be as abstract or as concrete as you choose.

Here's something from an online workshop that I teach at least twice each year: once in the winter, then again in the summer, and I’m pleased to say that it attracts some very fine writers to it, most of whom find their way to me through my work or by word of mouth. I’m told, by many, that it’s a workshop unlike any other, which of course pleases me beyond words. But anyhow, the exercise I think I’ll share here is called the 12 x 12 prompt, and I suppose it speaks to some of the things we’ve talked about in this interview: constraint, restriction, obsession, etc. I've had some rich results written in response to it. So here you go.

This assignment is an act in obsession, but not just with words but with, instead, numbers (yes, like math).

This is an exercise designed to shackle you, frustrate you, disorient you, yet liberate you too (I hope). And if nothing else to get you to slow the process of writing sentences (and stories) down.

Here are the details of the 12 x 12 story:

In this story there will be a total of 12 numbered sections.

Each section (of which there will be 12) will be made up of 12 sentences.

Each sentence in each section will be made up of precisely 12 words.

There will be no sentences, in other words, that are more than 12 words in length.

There will be no sentences, in other words, that are less than 12 words in length.

In each section—each section which is made up of 12 sentences, each sentence with exactly 12 words in it—you must make use of the number 12 (or the word "twelve") in one of your 12/twelve sentences. In other words, the number 12, or the word twelve, must appear once (and only once) in each of the 12 sections.

All together then, this twelve-by-twelve story will contain a total of 144 sentences adding up to a total of 1,728 words (not including your name and the title that you give to this story).

Just for fun (you're having fun, right?) why not add this final detail to this challenge: that the title of this twelve-by-twelve story should also number twelve (12) words in length.

So not counting your name (which isn't a part of the story anyway) this story (with the title included in the total word count) should come in at exactly 1,740 words.

In closing, do you have any advice for early writers? Or rather, what's something you would have liked to have known when you first started taking your writing seriously?

Get comfortable being alone. Seek out a community made up of birds or fish or trees. Don't let others tell you no. Don't let people or what you think other people want get in the way.

Any final thoughts / words of wisdom?

In the words of Barry Hannah: "Don't try to be wise." Write what you can't not write. Make it pleasing to your eye and ear. Find your fish. Find your bird. Find your mud.

Or what the Buddhists say might also be true: that if you encounter the Buddha on your path you must kill him. And to that I might add: and tell about it.