It’s a wondrous feeling to discover a writer by chance. Such was the case with my experience in finding the poet and collage artist Kathryn Cowles. Early last year, I was looking up a book by Andrea Cohen in my library’s clunky database, and Cowles’ 2008 debut collection appeared in the margins as a suggested ‘related’ text. Based simply on the title - Eleanor, Eleanor, Not Your Real Name - I was sold.

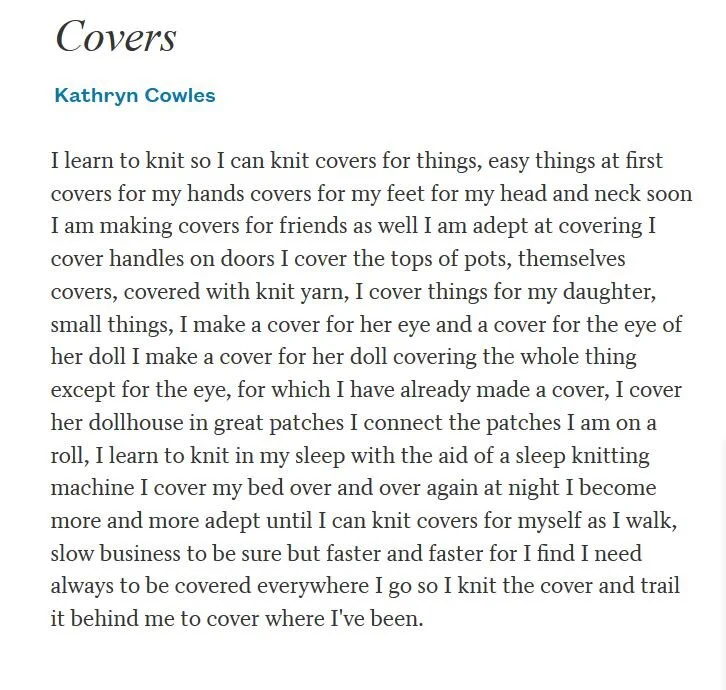

What started as a whimsical decision turned into me being fully immersed in her collection, where Cowles provided a character study through imaginative narrative poems, complete with her own cover art. When I finished the 2008 collection, I searched for more of her work, only to find that her follow-up collection, Maps and Transcripts of the Ordinary World, was released in March of 2020 by Milkweed. Maybe my library database knows more than I think.

After spending time with Cowles’ work - playful and inventive and documentarian and ambient and wholly original - I sent her some questions and we chatted about poetry, collage, ekphrasis, patience, and identical twins.

Let's begin with an icebreaker. What is the book that's nearest to you (in proximity, not adoration) and what's the last plant you cared for?

Oh, this is a first question I can get behind. I am sitting next to a bookshelf, which makes the answer tricky. If I’m being honest, the one that appears to be poking out the most is an oversized Prehistoric Actual Size book that belongs to my daughter that depicts, like, the toes of dinosaurs or bodies of enormous ancient millipedes at their actual size. If I’m being dishonest, the closest book is Donald Revell’s White Campion, which is a book I’ve been looking forward to reading for a very long time and that I intend to read as soon as I finish answering these questions, or maybe for a break in the middle, but that is technically just tucked in with the rest of the books, equidistant. For the plant, it’s a pot of clover I grabbed at the grocery store around St. Patrick’s Day in a sudden bought of festivity, and that is still somehow clinging to life, and of which I have therefore become unusually fond. Did you know clover leaves close at night and open in the day, like flowers? Well they do.

Some time last year, I read Eleanor, Eleanor, not your real name by chance at my library. It was suggested to me through my library's faulty algorithm, where it simply lists the next alphabetical author in that genre. I'd love to begin talking about this book. Maybe you can take us back to 2008 and the process of working on this debut collection, and not only a debut, but a cohesive project with connected poems and an ongoing title character / narrative.

This book-reading origin story feels very Eleanor to me. I have weirdly often heard of someone stumbling across the book by chance and then getting involved with it—this happens often enough that I have begun to think of it as sneakily self-willed, doing this on purpose. The book certainly snuck up on me and did what it wanted to with me. To answer about process, I started writing Eleanor because I kept losing people—like the Eleanor figure, or the mythologically tall Reuben, or Andy Smith, whose name is so common it’s impossible to track him down. Others too. These dear people would move or leave or just disappear over time or in one case join a religious cult and become deliberately uncontactable. So I had this idea that I could hold on to them, most especially Eleanor (which is not a real name), if I could pin them down to my page somehow with words. Even if the people I pinned were merely ghosts or shades, sort of haunting the book, at least I could hold them and look at them, rather like butterflies in a butterfly collection. But of course, poetry can’t bring people back to the poet, at least not in a live way, which is part of what I learned in writing the book. Also that books are better off when characters have their own strange agency, when they escape any trap a book sets for them. Eleanor is expert at giving traps the slip.

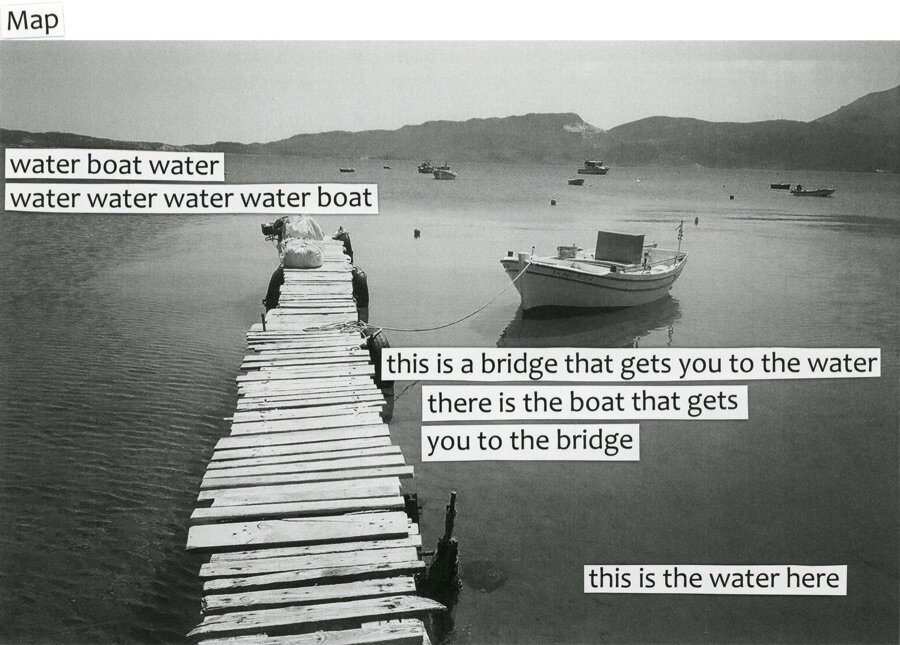

Congratulations on releasing 2020's Maps and Transcripts of the Ordinary World! I really admired the format and the seemingly ambient pacing. Here we have directions, we have postcards, we have transcripts of birds, we have field guides. It's almost as if you're approaching the poem from the lens of an explorer or traveler or researcher or, simply, someone finding their way. Do you have a history/fascination with these instructional ways of communication?

I definitely have a history with maps. When I was a kid (and still today), my mom loved maps and would hang them up all over the house and ask spontaneous obscure geography questions at dinnertime. We had geological maps and maps of the stars, literary maps and world maps and extremely local maps. I love the way each map is its own set of glasses for looking at the world. One map might be about rivers or railroads while another might be about relative hill height and other topographic understandings of landscape. And another map might just want to point to where birds like to go. I have long been fascinated that there are so many different ways of looking at the world—travel guides and field guides, recipes, photographs, directions. Paying real attention can look completely different from one form to another. For the book, I was interested in finding ways of recording the ordinary stuff of the world that weren’t the usual ways of lyric poetry. A different set of glasses (or a bunch of different sets). And it occurred to me at the same time that the documents of transcription and of science, of data collection and information dissemination, can sometimes veer lyrical. We’re trained to think of scientific language as on one end of a spectrum of speech, and poetic language as on the complete other end of the spectrum, but I like to think of it more like a wheel than a spectrum, where if you travel far enough into the scientific, it sudden turns poetic. Lots of poets love scientists, especially biologists, for their particular kinds of attention, which are, in and of themselves, a kind of lyricism. So sometimes as I wrote these poems I thought of them as mechanisms for helping me pay a different kind of attention than I was used to. I write best when my usual attention gets disrupted somehow.

While Eleanor seems to focus on the internal (the body, the spirit, the imagined, the real), Maps seems to really focus on place. And it feels much calmer and more meditative. Can you speak on place and perhaps, energy levels for both?

I have to confess, place is another thing I was initially writing about in order to hold it tightly to me—to keep it for myself. When I started the second book, I was being regularly wrenched away from places I loved (as opposed to people I loved, as with the first book) and forced to live in places I would not have chosen. And when I returned to the loved places, they were inevitably different. And so I initially thought, having apparently learned nothing from my first book, that if I could just write the places down, if I could just capture some essential thing about them and pin it to the page, then my book could be a little comforting Museum of Place, and I wouldn’t have to feel so sad. Nothing would be lost. It took some writing before I could realize a) that language can’t get the actual world to stick to a page, and b) how small such a world would be anyway, if it could—contained and sterile. The purpose of writing isn’t to substitute itself for the world, or render the world in fossilized form (I think of Emerson’s brilliant observation, “language is fossil poetry”). Indeed, the world continues worlding whether I write it down or not, and thank heavens. It can be a real comfort to realize that the poetry can’t hurt the actual thing. And what it can do is more complex than I originally thought—part comfort, part praise, part memory, part acting as a metaphor for something human.

Throughout your first collection and throughout your new collection, you showcase collage. You designed the cover for your debut as well as all of the art found throughout your newest. How do you approach multimedia projects like this? Is visual art always part of the conversation?

Visual art is for me another way of thinking. I frequently turn to it when I’ve been thinking about something and have hit a road block and need to think in a different way. It involves different tools from poetry and operates differently, and so it allows me to jump the ruts that my sometimes-obsessive brain makes for itself. I first started making collage poems—in which words and image are coequal parts, sort of wrestling with one another—right around when the Eleanor book came out, and those turned into the first poem-photographs in Maps. Lately, my collage poems are far more intricately worked on their surfaces, in the vein of the cover of Maps, which I also made. I’ve been using old cut-outs from 1950s and 60s magazines and typing up text on an electric typewriter from the 70s, and something about the combination helps me to speak sometimes in a voice that feels almost channeled, and to talk directly about things like the construction of gender that I’ve had real difficulty talking about in the past without sounding either high-horse-y or oversimplified. I’m interested in ways of saying complicated things as simply as I possibly can, and images can help with that. Susan Howe writes, “Poems are the impossibility of plainness rendered in plainest form,” and that has always struck me as absolutely true, at least of a lot of the poetry that is most dear to me.

With a debut in 2008 and your follow-up in 2020, I’d love to know what your writing routines and collage art routines looked like then and now. Were you forever tinkering? Do other manuscripts / projects exist?

Between 2008 and 2020, I got my first academic job, burned out, got my second academic job, had a difficult baby, then a few years later had identical twins. So my process has changed utterly over a fairly short amount of time. I used to write only very very late at night, usually while drinking rocks whiskey, a habit I learned in graduate school, where it seemed to me very cool, and I truly thought the lateness and the whiskey were both necessary to my process, and I wrote a lot of poems this way, and very few of them were any good, which meant I was prolific at filling notebook pages, but very slow at producing books. When I had a baby, things were suddenly not possible that had been possible, most especially choosing when I got to sleep, and I had to adjust, and the adjustment has been good for the work, honestly, even if it came at a moment when I had less time than ever for writing.

I work best when I don’t know what I’m doing or when I’m thrown off routine. For instance, I remember that to get my first daughter, who was an unusually, exhaustingly fussy baby, to go to sleep at night, I’d have to sit in the dark for an hour and a half nursing her, then creep over and put her in her crib and just pray to every imaginable god that she didn’t wake up in the process and force me to start all over again. If I tried to look at a computer or watch a movie or read a book, the light would wake her. It was so frustrating. I tried to write poems in the pitch dark, but I couldn’t read my own handwriting later. And so I innovated. I started writing poems in my head. They were image-driven because that’s the only way I could remember them. I would add a line or two, rooted in image and then go back and rehearse all the previous lines, then add another one and just repeat the whole thing over and over in my head, then I’d carefully put the baby ever so gently in her crib once she was asleep, and then I’d run downstairs and try to write it all down before I forgot it. Which obviously changed the poems completely in terms of structure, in terms of pacing.

I had another project—one I’m really grateful to have done but that was less about product than process—where I would sit by Seneca Lake every day until I could get a poem to come out, and then I’d write it down and take a bland photograph of the view from the same spot and leave. I started the project after reading a couple of books by Larry Eigner, who had cerebral palsy and so for many years wasn’t able to leave his house much and wrote most of his poems from a single glassed-in porch with a single view. At the same time, I was looking at paintings by Cezanne and others of the same mountain or cathedral painted again and again in slightly different light or weather, and thinking about people who could look at the same thing day in and day out and write it or paint it over and over and have every iteration feel alive and true. I didn’t think I’d be able to do this because I get so bored with my own head and my own looking, so I decided to try it and track the ways I failed, because that’s how my brain works. I expected a two-week project, but it grew and grew into two months, and then a whole season, and before I knew it a year had passed, and I’d been going out to the same bench almost every day, and I had hundreds of pages of writing. Though I’m not interested in wrestling the poems into book form (who can write a good poem every day, after all?), this was one of the most important years of my life to my concept of writing, my process. I learned, for instance, that a poem will turn itself on its own if I just sit and let it, which was a revelation. I learned a kind of practice and rhythm, a kind of faith in the poem, that has made it possible for me to write poems now that are tighter but also wider in scale.

With Maps being out a little more than a year, can you discuss what you're currently working on?

I’m writing a series of fake ekphrastic poems from an artist figure called, believe it or not, Eleanor Eleanor. (Side note: Originally I was using my own name as the artist, in the grand history of playing the line between fiction and autobiography, but that got confusing for poor journals that kept asking to publish my artwork alongside the poems. And Eleanor has become a kind of doppelganger for me anyway, and so it made a certain amount of sense to tongue-in-cheek the title of the first book into a full name.) The poems are written from the perspective of the artist, describing her art. The art pieces are completely invented—some of them physically impossible or at least terribly unlikely or dangerous. Many of them operate the way metaphors often operate in poetry. They are a museum of metaphors, of images that represent my own thinking and feeling. The poet Elisa Gabbert recently completely startled me by choosing a group of the poems from this manuscript to win the Alice Fay di Castagnola Award from the Poetry Society of America for a manuscript in progress. I have trouble telling if my own poems are worth a damn or not when I’m in the throes of them, so it was a great relief to have a writer I admire say very publicly that they were actually good; Gabbert’s citation for the prize feels, as I said at the time, plagiarized directly from my soul, it explains so clearly what I was trying to do. Which is massively affirming.

Along with poetry and collage, do you have any other interests?

I write songs and have recently acquired some recording and mixing skillz (with a z), having apprenticed myself to a couple of wonderful local sound engineers. I like to make extremely elaborate and whimsical Halloween costumes for my children based on their own drawings. I like to research fascinating twin lore. I like to make Greek food. I like to look at birds on the feeder out my window. I like to read other people’s poetry books. I like to take naps at ill-advised times of day. (With my sweet aging dog.) I like to write letters to people and to make my own postcards.

via poets.org

What books / albums / movies have been keeping you company during the pandemic?

Mary Ruefle’s Madness Rack and Honey—this one will be a favorite for my whole life. Mary was the writer in residence a few years ago for the Trias Residency, which I direct on rotation, and she read an essay once during her semester here that had me rolling with laughter even as I cried listening to it. Sarah J. Sloat’s Hotel Almighty I stumbled across during the pandemic and proceeded to love—it contains terrific erasures both in terms of language and also visuals (so often such work is only terrific at one or the other). Yoko Ono’s grapefruit is one of the great pieces of conceptual art of the 20th century, in my opinion, and it’s been both influential and calming in recent months. I was reading and rereading Kiki Petrosino’s brilliant White Blood for a couple of months there. I’ve been re-watching some dear old movies like “Wild Strawberries” or, in winter time, “The Bishop’s Wife.” There’s something about the oldness of the normalcy in black and white films that helps me to disappear into them, unlike more contemporary movies that could be mistaken for present-day, where I get all nervous about people walking around without masks on or standing too close to one another or, you know, kissing. I was listening to a lot of Nina Simone last summer and fall as a sharp soundtrack to the worldwide protests around race. More recently, I’ve been kind of obsessed with Sharon Van Etten’s Remind Me Tomorrow and some similarly veined musicians (Angel Olsen, Big Thief) and have allowed myself to focus more on obsessively re-listening to albums I already love during the pandemic than on discovering newer stuff. Safety in the familiar, I guess.

If you can, provide a photo of your workspace or describe with words. What are some essentials while you create?

Today I wrote a poem while walking, so my workspace was full of birds and flowers. But I often write either from my kitchen table, facing my leafy Finger Lakes backyard, or from my double-sized standing/sitting desk that’s usually covered with various kinds of glue and paper clippings and stacks of books and half-finished abandoned things. I usually have to clear out a notebook-sized space in order to write anything down. Right now I’m writing this from my couch because it seemed like too much effort to clear out a whole computer-sized space.

For this ongoing author interview series, I'm asking for everyone to present a writing prompt. It can be as abstract or as concrete as you choose.

Get under a table or bed. Or up a tree. Or sit on the floor of a closet under the dangling clothes or in dry bathtub. Anywhere strange where kids go but not grownups. And then think about when you’ve been in such places of strange perspective before. Lying under my table, looking at the bottom side of it, I think, for instance, of the circular clothes racks of departments stores I’d sneak into while shopping with my mom as a kid—how quiet it is when one is surrounded by orderly clothes, peeking out through the hangers. I also think of the time when my dad was dying of the flesh-eating bacteria (don’t worry, he made it through), and I was in a stereotypical awful hospital waiting room, with a tiny loud TV high on the wall blaring, lying under one of those side tables with a fake drawer with gold fake pull, looking at the underside of the table and the factory tags for its production and thinking of what it would be like to have a dead dad. The goal here is to use the fact of being in one strange place as a kind of teleport to get you to remember another strange place. To metaphorize your self elsewhere or elsetime. I believe strange kid places can blur time. And you can’t cheat by just imagining yourself on the floor, etc. You’ve got to actually get on the floor.

In closing, do you have any advice for early writers? Or rather, what's something you would have liked to have known when you first started taking your writing seriously?

I was about to say I would have liked to know that I would always fail to do the impossible thing I set out to do when writing a book (get lost people back! retain loved places exactly as they are!). But then, it turns out the books are about the humanity of such failures, about how we can’t have these things we want, at least not in the way we want them, and that it’s probably better that way. I think I learned about being a human being in writing the books. They were devices for thinking with, processes, so it would have been ruinous to the poems to know the end point of the process beforehand. Which is to say, sometimes the thing a poet has to learn in the writing of the book can’t be given to them in any other way except in writing it. And it’s a hard and unwieldy way of getting some scrap of wisdom, and I frequently think I’m completely lost, but being lost is better for writing than knowing exactly where one is. So many that’s the advice: Allow yourself to be lost. To have no idea what the hell you’re doing.

Any final thoughts / words of wisdom / shout-outs? Thank you!

Thanks for the unusual, interesting, thoughtful, and specific questions. This was a real pleasure.

via DIAGRAM