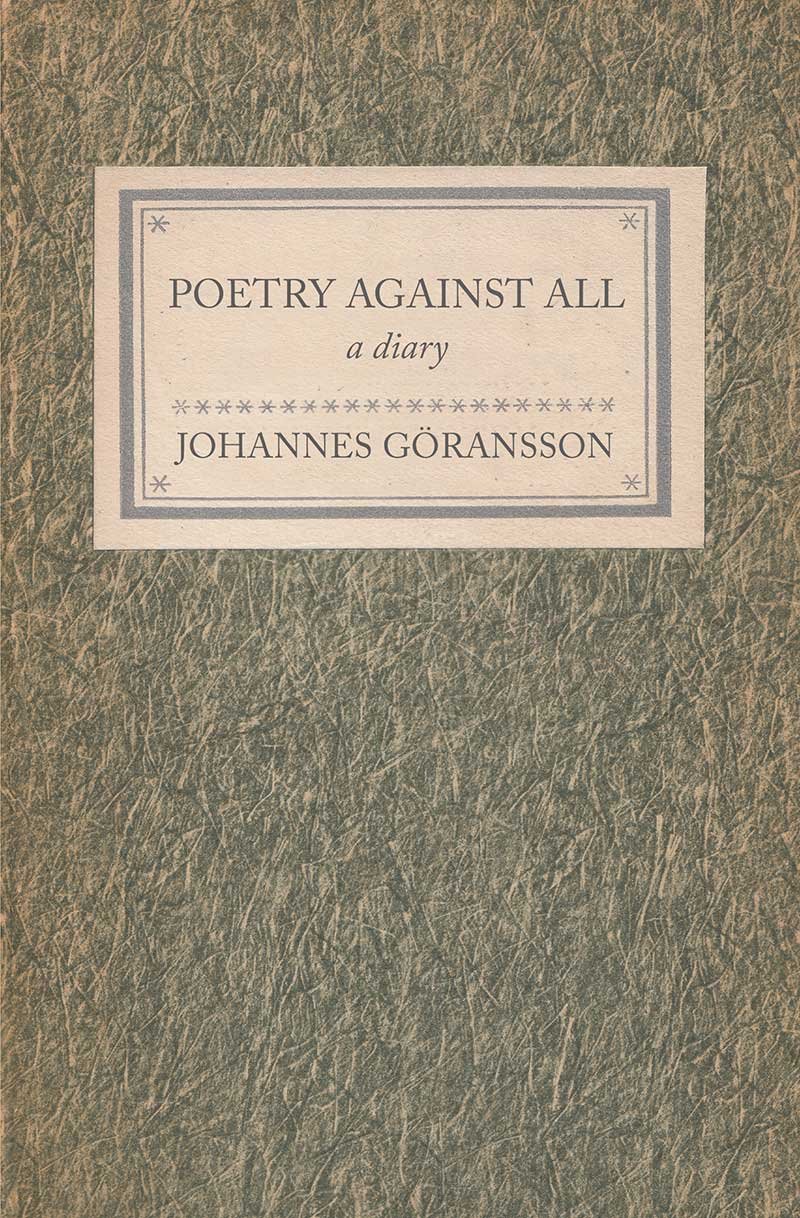

Johannes Göransson is a poet, translator, and Notre Dame professor. Born and raised in Sweden and now residing in South Bend, Indiana, Göransson has released a collection of essays on translation as well as many collections of poetry - some as letters, some as diary entries, some as theatrical dramatic monologues. Along with teaching and working in translation he also runs Action Books with his wife, the author Joyelle McSweeney.

Each collection of Göransson’s feels like its own investigative, poetic rabbit hole. To begin reading is to be swept up in lust and disgust, the grotesque and the divine. A mineshaft of both gathered corpses and jewels.

In previous reviews, I used lines like “letters of messy imagination” and “a whirlwind of language” and “fragmented fables gone wrong” and, lastly, “Debauched gods under a tar-soaked sun. Rip open my skull for I am in love.”

I spoke with the author over email and we talked about the prose poem, occult studies, Taylor Swift, and multiple languages bleeding onto the same page.

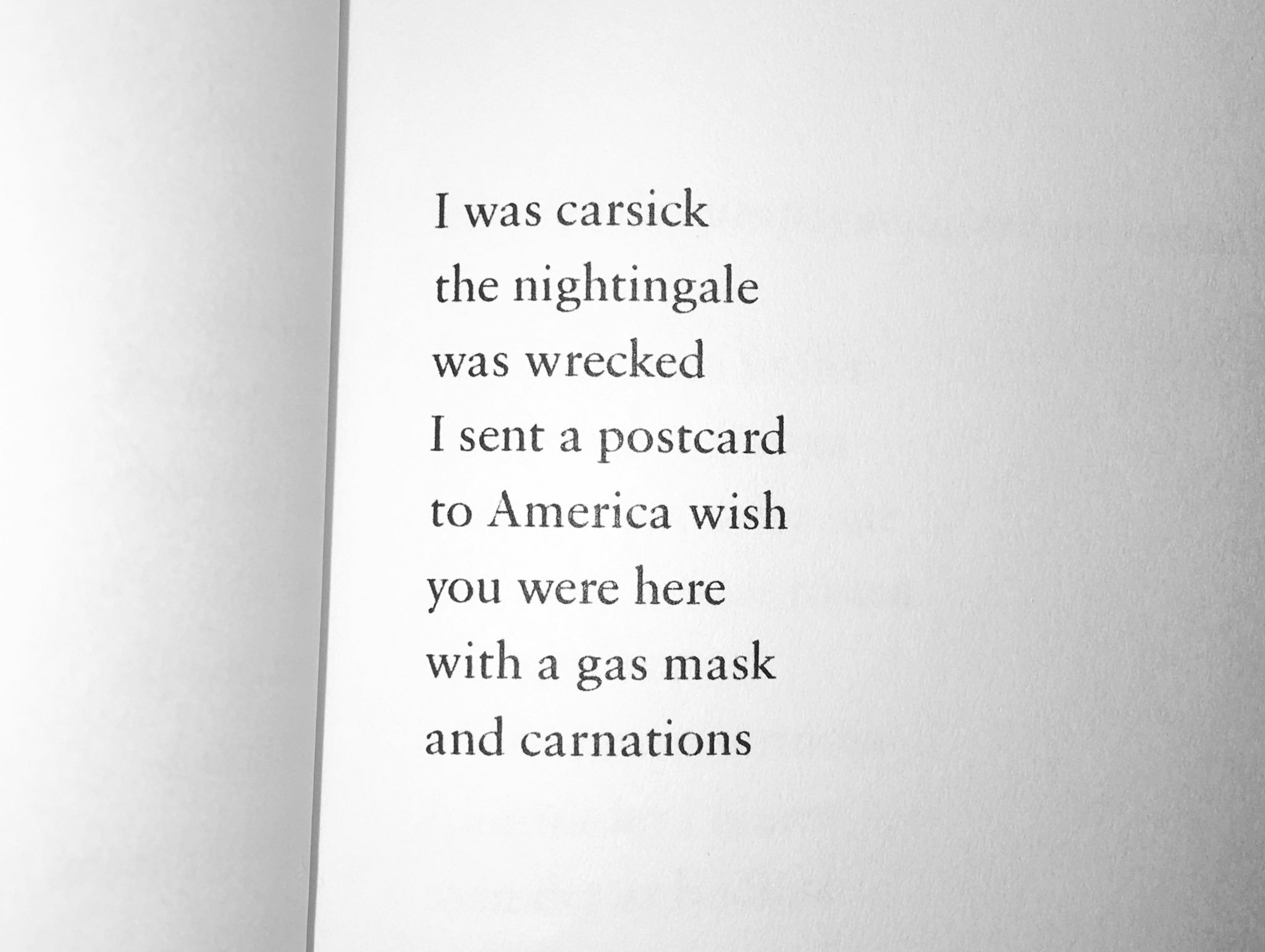

from Pilot (2008)

As an icebreaker, what film (past or present) or filmmaker (living or dead) would you like to shadow for a day? Standing on set, sitting in the writer's room, etc.

Would love to see the production crew make fake snow for The Shining. Or watch Jack Smith when he painted the trees for Normal Love. Or to be at the mental hospital in Norway when they showed Dreyer's Joan of Arc. Or to help Kenneth Anger cast a spell on Mick Jagger to get him to make the soundtrack to Invocation to My Demon Brother.

Starting at the beginning, I'd love to hear a bit about your early writing process. Translation aside (we'll get to that shortly) in 2007 you released your debut poetry collection and in 2008 you released two other collections. What was that time like? You hit the ground running, it seems.

I wrote Dear Ra back in 2000/2001 just after I graduated from MFA school. Then I spent a few years where I was really broke and worked in a tough and exhausting blue collar job, during that time I gathered a lot of ideas but I didn't have the energy or time to really write them down. Then in 2003 when I entered PhD program, it all came flooding out because suddenly I had so much time and energy. So that's when I wrote Quarantine. Then I wrote Pilot right before it was published. It was inspired by doing a lot of translation; it is in some ways the residue of translating, a poem of mistranslation and potential translations. So basically, yes, I was really in the zone at that time but one book was from a few years before.

Following Pilot, your collections have all been prose poems / prose blocks. Is this a style choice you see continuing forward?

No, I feel like I've done what I can with prose poetry for now. If my interest in prose poetry came from a desire to keep going, to go further without the interruptions of line breaks - and along with it what I then perceived as a kind of preciousness - I am now interested in the strange rhythms and music that can be generated by interruptions, stutters, cuts, gaps. In some ways I've been interested in the very preciousness I used to despise. While I used to want to write poetry that was unencumbered by the poetic, I am now more and more interested in the poetic. Not the poetic of the status quo - which is really just moderation - but poeticism as a scandal.

I know earlier this fall you were questioning the uptick in popularity with the prose poem and prose poetry in general. What personally brought you to the prose poem? And what kept you coming back?

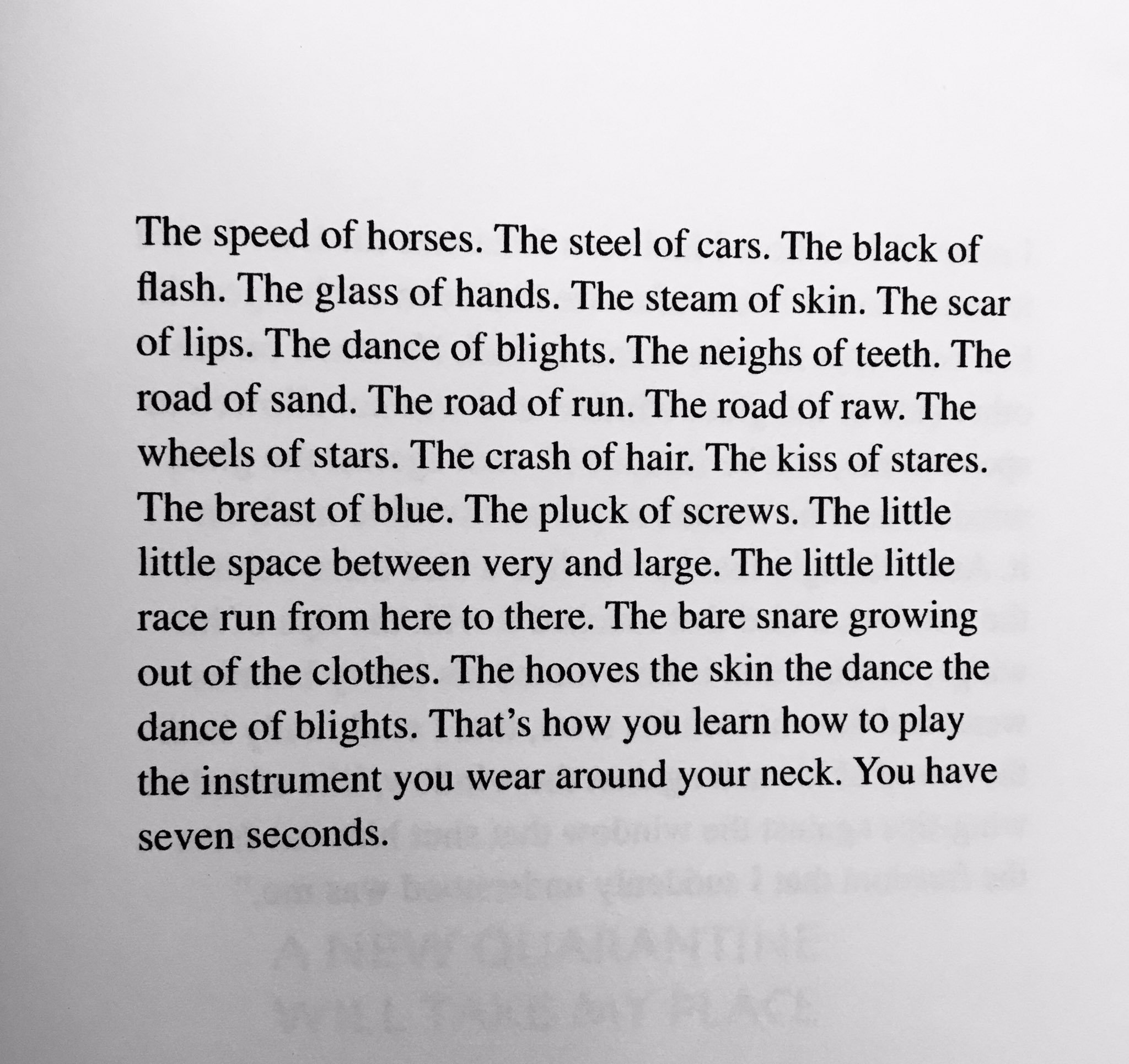

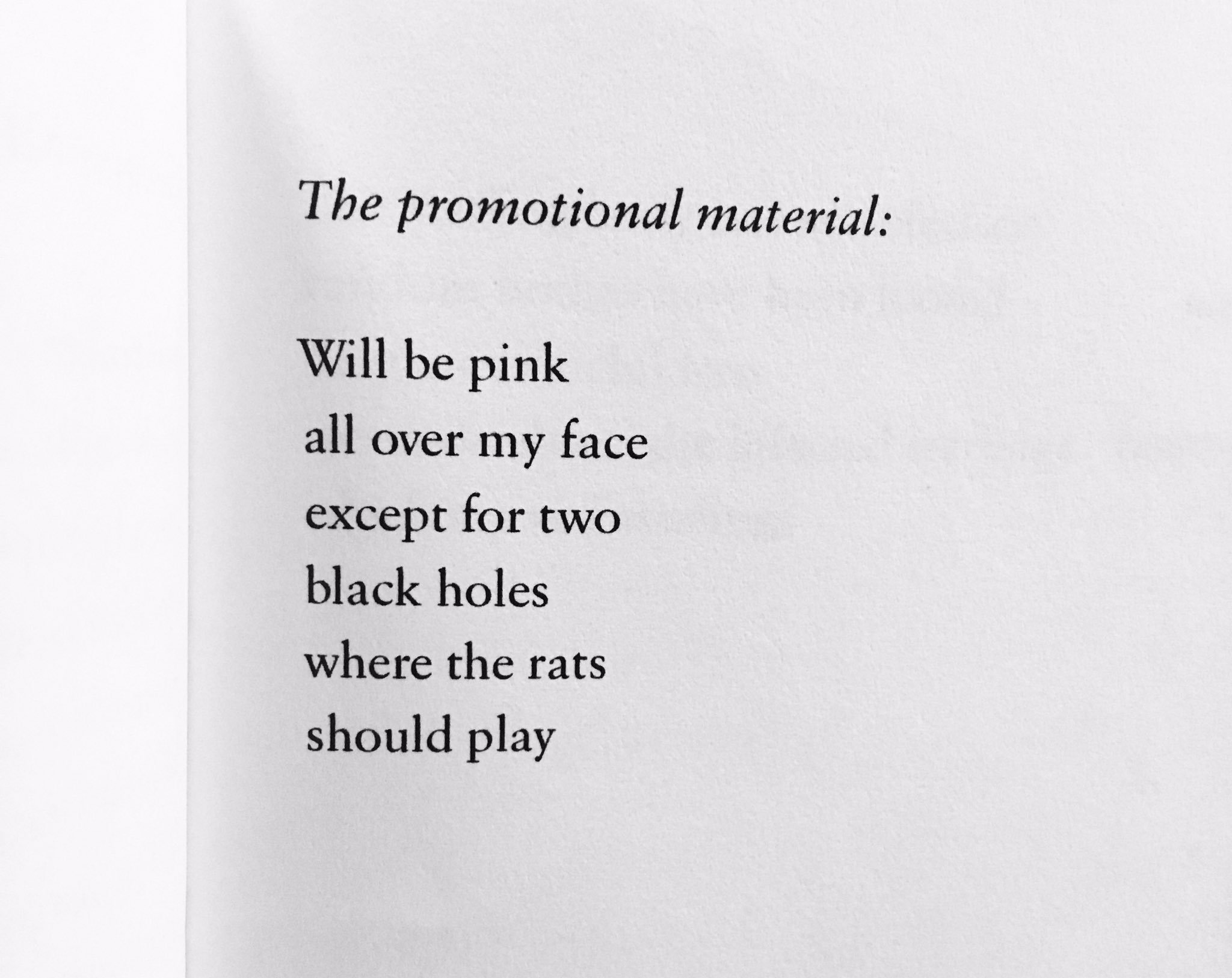

This goes way back to when I began writing and loved Rimbaud's, Lautréamont's, and Baudelaire's prose poems. Then Aase Berg's and Ann Jäderlund's prose poems. What always drew me to prose poetry was as a mode of intensity, a mode that allowed me to just keep going. I really developed my fundamental mode with Dear Ra, which was prose poems, but in difference to most prose poems at the time, I wanted to keep going. So I went for many paragraphs. I wanted to keep going, not to leave off at after a lyric moment, but to continually turn and twist and dig in. And that's even more evident in New Quarantine - which has titles and cinematic intertitles, but which can be read as one long montage. I wanted to just keep going, without worrying about line breaks or anything like that. I also wanted to marry my love of Surrealism with a kind of manic New York School energy - especially Ted Berrigan - that I both loved and felt totally at odds with. But I also think that my prose poetry is all pretty different. For example, Entrance to a colonial pageant in which we all begin to intricate is dramatic monologues, The Sugar Book takes perverse pleasure in lines that run out of steam, exhaust themselves, and Haute Surveillance is the most novelistic. I guess POETRY AGAINST ALL is also written in prose, but those really were diary entries, but maybe that counts.

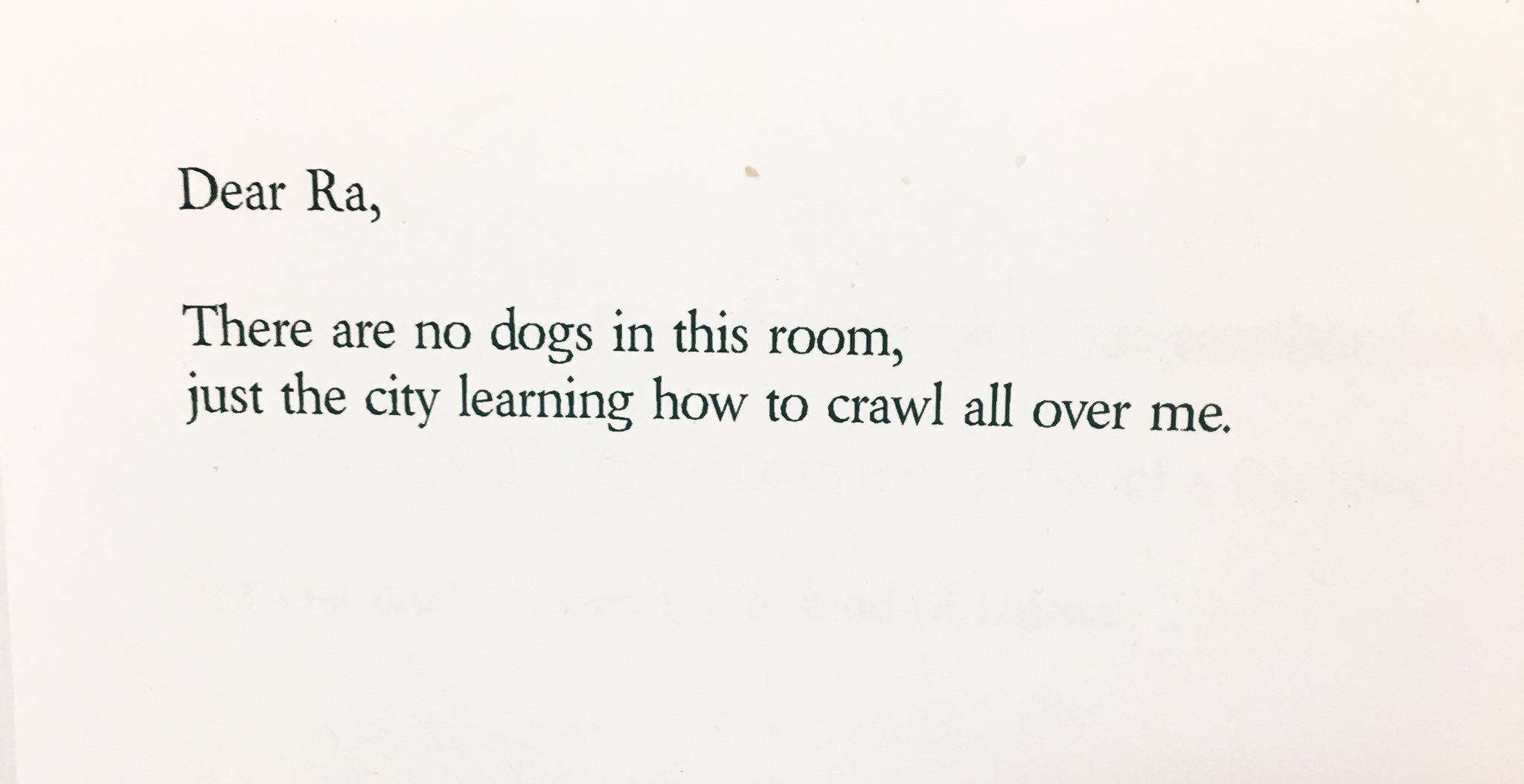

from Dear Ra (2008)

In regards to your own writing, what are you currently working on?

I finished a book I worked on for several years, Summer, which is coming out next spring (from Tarpaulin Sky). It's a translingual book-length poem that started being about linguistic pollution and deformation and homesickness, then it became about fascism and what it has to do with pollution, then it became an elegy for my daughter Arachne, then became a meditation on police brutality and the debt economy (and debt aesthetics), and then it became about my son Othello and toxins (a more literal version of the pollution I was first writing about). But maybe most of all it's about the strange rhythms that resulted when I brought Swedish and English together. That book took everything out of me. Left me completely husked for months.

Lately I've just been experimenting with language, coming up with new ideas. I've written a few hundred pages but they're not poems yet. For a while I thought I was working on a sci-fi novel but it turns out that was just a parable I needed to tell myself - or which I needed my own writing to tell me - about death. I guess I had to understand death better. I had to understand that I was going to die in order to start writing again.

Switching over to translation, having done it for nearly two decades, does it get easier or is each project its own beast? What are some parts of the process that still might cause you to pause?

Every project is its own beast. I have to be drawn to the poetry to translate it. Sometimes I'm asked to translate work I'm not 100% involved in and I just can't. Or I do a poor job. The process is intricately connected to the act of reading and writing for me.

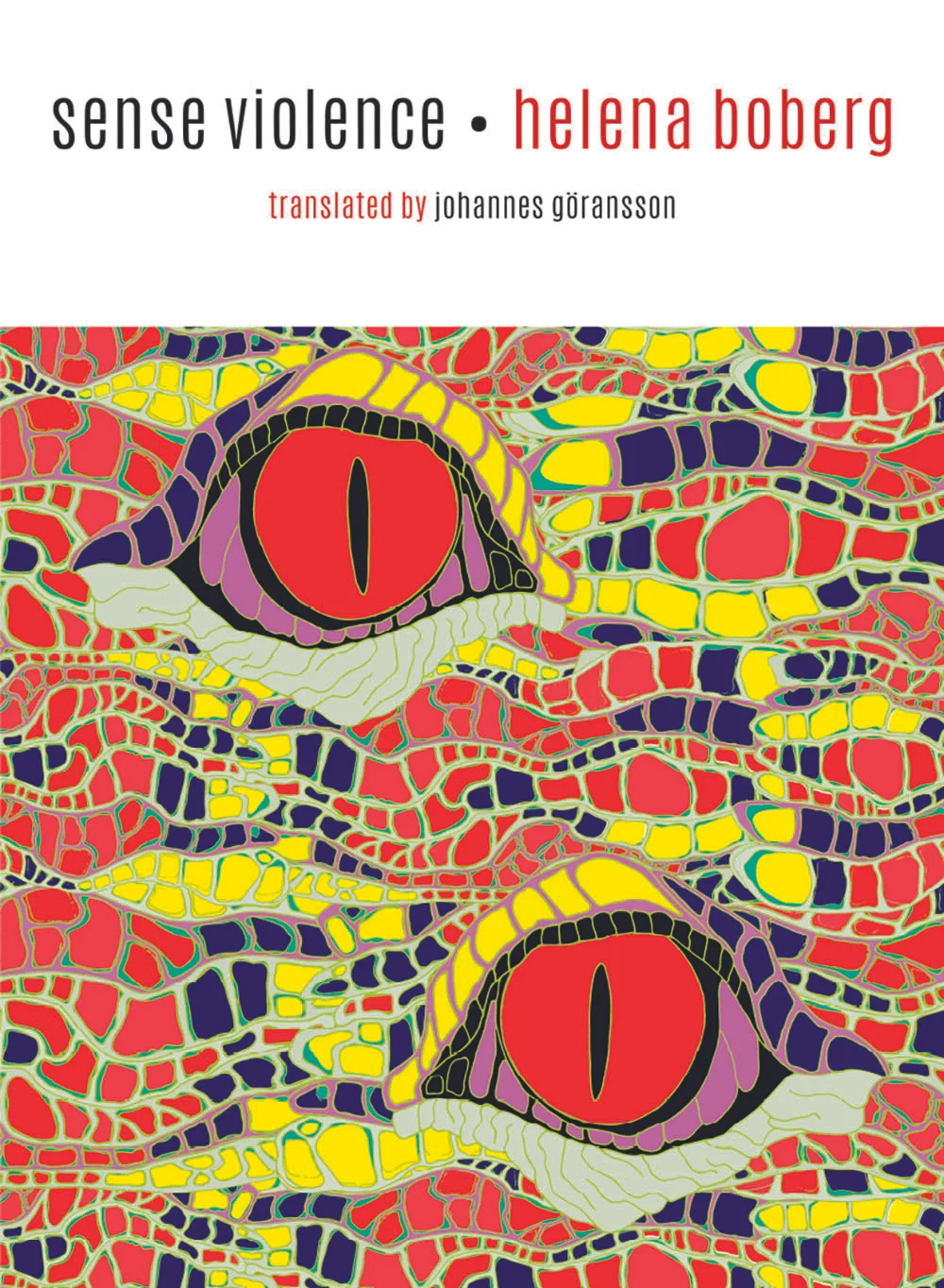

You translated and released Helena Boberg's Sense Violence last year and it was her first full-length English translation. I'm sure there are many poets you want to see translated into English. How do one choose such an undertaking?

I don't translate for a living, I do it all for pleasure or something like that. It usually starts just with my reading the book. I become involved in it and then I inevitably start translating it in my head and from there I might go on to actually translate it if I feel like I have the time and space to do it.

Are there other writers you are currently translating?

I just translated Eva Kristina Olsson's The Angelgreen Sacrament (coming out from Black Square Editions this winter), which is a kind of possession or channeling poem about encountering "angels." It's an occult masterpiece, and incredibly involving as a translator. It's a book that channels voices and it's a book that asked me to channel it as well, to really bring this inhuman voice into my body. I've also recently translated Ann Jäderlund's Ensamtal (which I translated as Lonespeech but which could also be Onedialogue or something else, it's a very rich, punny title), which is a rewriting/rewiring of the correspondence between Celan and Bachmann. Jäderlund is arguably the most influential contemporary Swedish poet, but it's hard to find presses who are interested in this kind of extreme work - these slender, short little poems charged with puns, syntactic tweaks, noises. Short poems of great intensity.

When you are deep in a project involving translation, do you find your own writing echoes similar voices/sentiments/landscapes? Or are you unable to write new material at the same time as focusing on translation? Perhaps a better question is how do you juggle the two? I'm curious to hear if/when those worlds blur and melt and drip into each other.

I get profoundly influenced by the work I translate - I think Summer was very much influenced by translating Boberg's Sense Violence and reading all of Olsson and Jäderlund (Helena has translated my Summer into Swedish, so that puts an interesting spin on things). But I'm not only influenced by the original; I'm most of all influenced by translating the poems. That is to say, I'm influenced by my own engagement with the foreign text, by bringing it so close to me, bringing it into my body. So in a sense, I'm influenced by myself. To use a phrase Joyelle and I took from Aase Berg, the poem is a "deformation zone": Translation really reveals how complex issues of agency are when it comes to writing. That's why it's so important for me to pick translation projects that will work with my writing.

You're a professor at Notre Dame and have been living in South Bend, Indiana since the mid-2000s. As I was born and raised in the area, I'd love to hear your thoughts on Michiana and being in the "Crossroads of America". I feel like you and Joyelle have managed to put South Bend on the map as a notable location for publishing poetry and translation.

South Bend is a complex place; sometimes I love it, and sometimes I hate it. I try to make a life for me and my family here that's as interesting and safe as I can. As for being a notable for publishing poetry, I am incredibly proud of what Action Books has published over the past couple of decades. We have published so many crucial US and international poets - Kim Hyesoon, Hiromi Ito, Ursula Andkjaer Olsen and more - but it's also true that the longer I work on Action Books, the more I realize how hard it is to take an outsider position that positions you against the establishment. The establishment is a system and systems seek to perpetuate themselves - which they do continually. So I don't know how notable we've become. Running a press that runs against the grain of prize culture etc. can be exhausting. But it can also be thrilling.

Outside of your own writing and translation, what have you been reading/enjoying as of late?

Will Alexander's massive new book, The Combustion Cycle (which I wrote about here), the collected Celan in Joris's translation (which I wrote about here), anthropologist Michael Taussig's writing, particularly his discussions about mimesis, Jonathan Culler's book Theory of the Lyric, and Eva Kristina Olsson's movies, performances and plays, particularly her reenvisionings of Medea and Antigone. Right now I'm reading Joy Williams' spectacular novel Breaking and Entering, which has some of the most beautiful use of dialogue I've ever come across.

Away from the page and into other art, what albums, artists, plays, films, multimedia, etc. have captivated you in recent months?

I've been listening to the podcast Weird Studies. I like the hosts' occult, unorthodox approaches to work across genres and media. I don't write for a special audience - I am drawn to the volatility of writing, how it gets interpreted in unintended or surprising ways by readers one may never have envisioned - but I do need to know that there are readers out there willing to engage and transform, be transformed by weird writing.

Lately my 2 year old has gotten me into classical music. He watches Little Einsteins, which always features classical music, so he demands "where's my violins" when he gets into the car, so we listen to the classical music stations and for the first time I'm really thinking about that kind of music, how they move. Yesterday I heard a really incredible and dramatic piece by Prokofiev which was fascinating, at one point it seemed to completely collapse, shatter, but it managed to go on.

If you can, provide a photo of your workspace. What are some essentials (coffee, wine, cigarettes) while you create?

Just coffee and a lot of different books (books of poetry, occult histories, insect anatomies, geology, kidnappings, etc.). I can't write after drinking and I don't smoke anymore though sometimes I fake smoke with a pen or pencil, and sometimes that helps. I often listen to pop music. Pop music with good sentences like Taylor Swift, Motown girl groups from the 1960s, Cornelis Vreesvijk, etc. Not necessarily the music I like most, but the songs with sentences with which I can do stuff.

For this ongoing author interview series, I'm asking for everyone to present a writing prompt. It can be as abstract or as concrete as you choose.

Write a poem that scares you. Make it 3 pages long. Write a sequel. Write another sequel. Make it about your body.

In closing, do you have any advice for early writers? Or rather, what's something you would have liked to have known when you first started working on your first book(s)?

Continually seek out writing that thrills you, but also try to figure out how to get something from writing that may appear boring or odd at first. Sometimes I think I developed more as a writer from poets whose work I didn't really like, who seemed opposed to my inherent tendencies, than from the poets I loved instantly. Allow yourself to be utterly influenced by others. Translate. Read works in translation. Forget about prize culture. Find people you can have good discussions with. Have the discussions.

Any final thoughts?

Wear a mask.

from Pilot (2008)