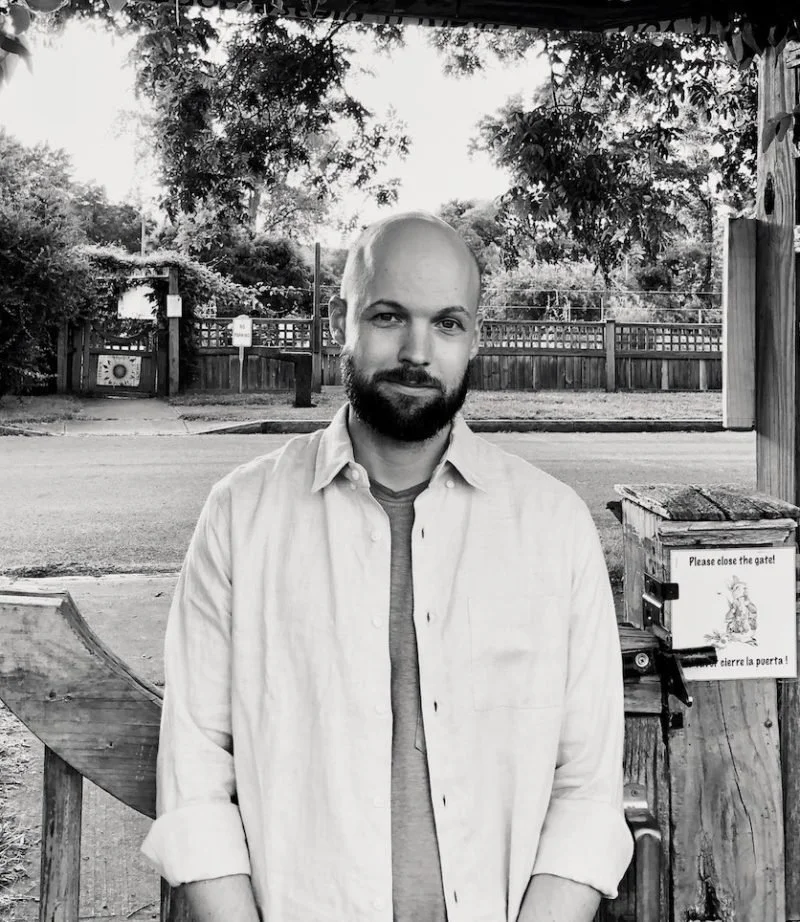

Photo: Evan Brown

The signature black hat, the black framed glasses: I notice them the instant I step off of the elevator for an interview with Chicago native Kevin Coval. He is seated on the fifth floor of the West Loop's Soho House, appearing calm and relaxed. I arrive right on time and he's already waiting for me.

To provide a brief overview, Kevin Coval is an educator, a wordsmith, an organizer, and a mentor to many. He is a published author. The kind of multitasker with 1,000 notes in his calendar yet still hungry for 1,000 more. After hearing a spoken word performance during a Sofar Sounds event back in September, I went home and properly did my research, only to find out that I've seen Coval's name all around town since moving here three years ago. From a music video with The O'My's to a book that he edited sitting on my shelf (The BreakBeat Poets: New American Poetry in the Age of Hip-Hop) to a play about graffiti artists, Coval's history with the pen runs deep.

When I listen to Coval, he is both selfless and humble; almost all of his answers are about benefiting the youth, enhancing education, letting unheard stories be told and untold neighborhoods be heard. He is perhaps best summed up in his own words:

“I’m interested in creating tools that help people think and engage in the world in new and different ways.”

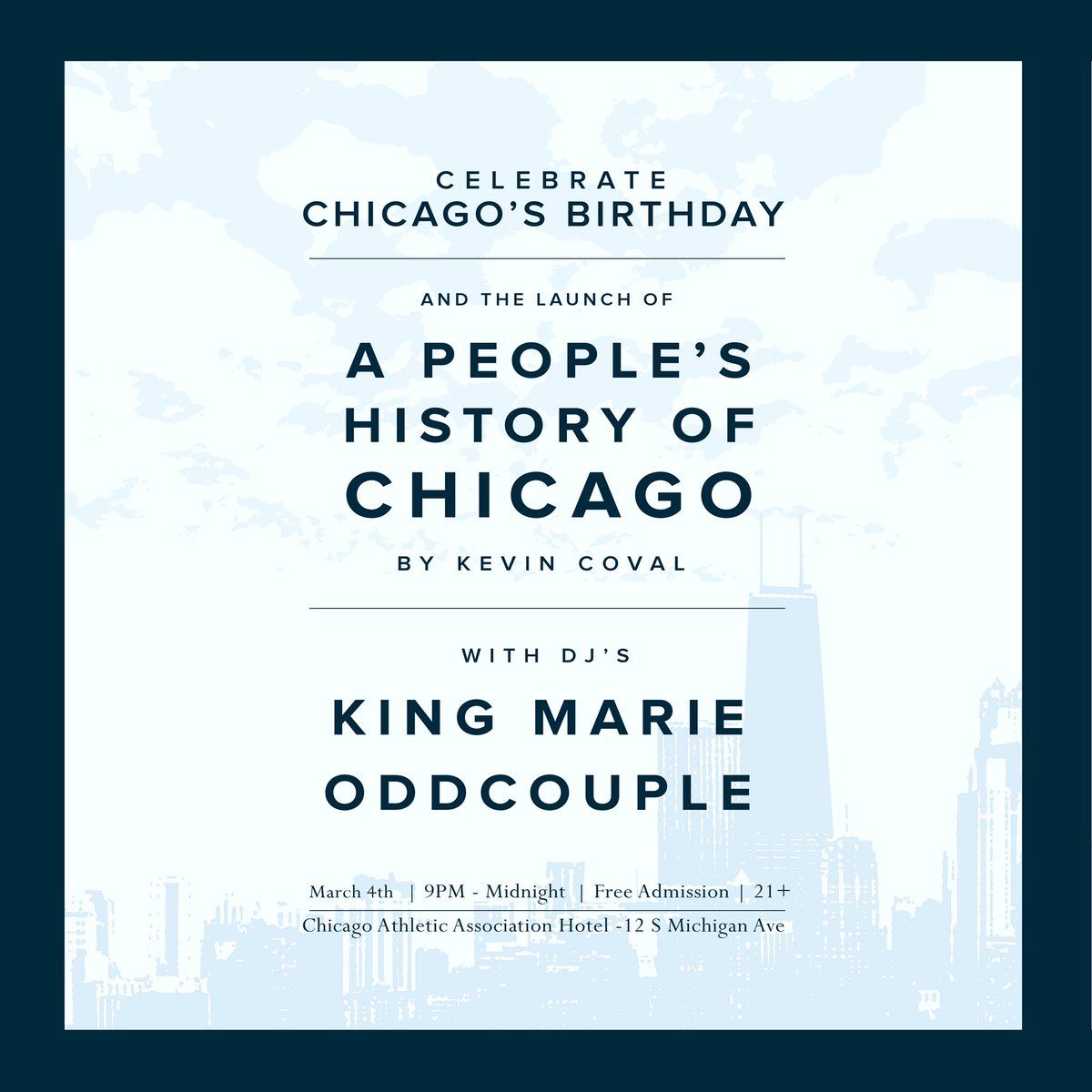

The day that I speak with Coval is the same day as his Chicago Next event; a monthly series at Soho House where Coval helps to facilitate musical performances and open-minded conversations. For the month of March, artists Qari and Rich Jones are on the bill. The reason that we're speaking, however, is not about Coval's musical interests (although at one point in the interview he calls Smino's project 'an aesthetic workshop'), but in fact about his newest book of poetry, The People's History of Chicago. It is a collection that chronicles the third largest city in the country in 77 poems, a number that represents every neighborhood in the Windy City.

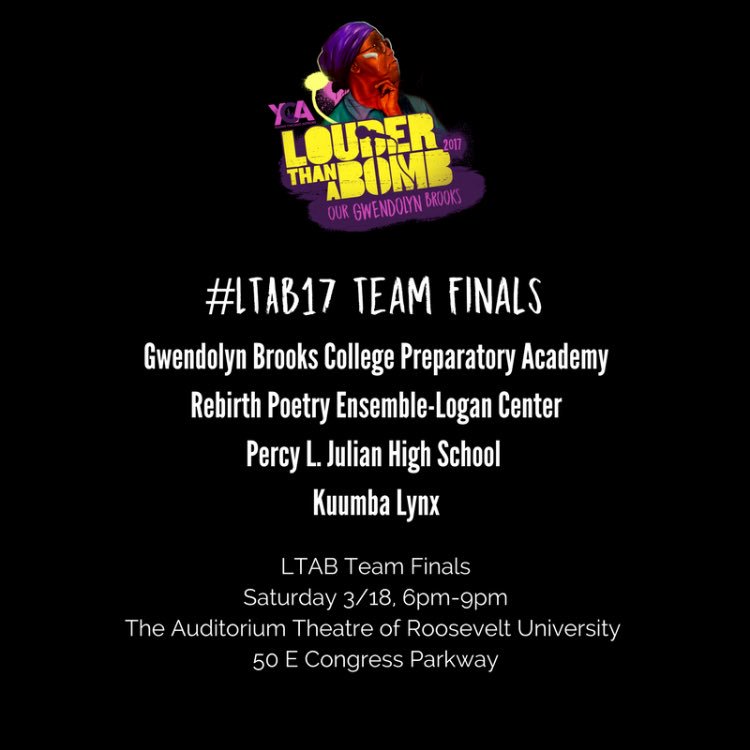

“In some ways, I wrote the book in order to be a history and English text. I really want to get it in the hands of educators and work with them on a curriculum and see how it can live inside of those spaces.” He tells me how the Lannan Foundation bought 2,000 copies for CPS teachers, as well as a copy for every student in Louder Than a Bomb, the world's largest youth poetry festival that Coval co-founded.

It is a daunting task to write about the history of a city both influential yet corrupt; powerful yet greedy; forward-thinking yet repetitive; multicultural yet Midwestern. Kevin Coval took it under his own responsibility to craft his telling of the history of Chicago. From Native Americans settling way before the white man, to Sun Ra, to the CTA's first track, to juke music, to Chief Keef performing at Lollapalooza.

“I sat down to really write a book about Wicker Park in the 90s and what I did was kind of unfurl how we got to this moment in gentrification and de-industrialization. That's what kind of propelled me into going further and further back. I wanted to connect these larger dots and narratives. Having to answer the question of whose space and city is this for real? And what kind of city ultimately are we seeking to create collectively if we continue to push out the cultural innovators and makers that have made this city so great and have made people want to move back to begin with?”

Coval's words are that of struggle, of uprising, of political upheaval. He talks race, he talks government, he addresses significant problems with an honest, poetic voice that shouts from the roofs of the city's skyscrapers. Find him clutching a microphone or a megaphone and providing verse about the corruption of Mayor Daly, the Chicago Cubs, the Cabrini Green housing projects, all with the same whirlwind wisdom. Although the book is finished and out to the masses, Coval is far from taking a vacation.

“I'm trying to do 180 readings in 365 days. The 180 readings are taking me to every neighborhood in the city. Intentionally. I'm doing at least one reading in every neighborhood. Through YCA, we're booking these readings and workshops. A lot of [it] will be trying to get people to fill in these gaps and also tell their own stories or insert their own interests or their own histories into the people's history of the city. ”

While his newly released 77 poems cover Chicago, Coval tells me how the book he is currently working on hones in on Wicker Park in the 90s as well as New Town in the 60s and 70s, both neighborhoods where he lived and experienced gentrification first-hand.

“We are repeating these things. There's something in the American psyche about necessity for historic and cultural amnesia. The history is so brutal and horrific that I think that there is a whitewashing in some ways to not go mad or to not create constant revolutionary change. The education system is bent intentionally to not want us to remember because if we remember then we would break these cycles that we continue to perpetuate.”

“We don't even pronounce the name of the city correctly," he continues. "These are the names of streets. We're holding them as heroes and they're butcherers.”

I briefly detail how growing up as a male in the Midwest, I wasn't taught that poetry was 'cool' or 'entertaining'. It was always a chore that I didn't discover a love for until my college years. I ask him how he is able to grab the attention of the youth through words of poetry.

“Thankfully, we're in a different time. I thought that as a kid and then Big Daddy Kane said he was a poet. After that, we were set as a culture. Before then, there was an intentionally narrow canon keeping the best and most engaging poets out of our education system. Thankfully, hip-hop brought me to the library to read the Black Arts poets for the first time, and who's cooler than Don L. Lee who later became Haki Madhubuti? Or Nikki Giovanni or Sonia Sanchez or Jayne Cortez? These were very cool sounding, looking, incredibly brilliant people who were turning verse, for me, on its head. I knew poetry at that time could be alive and in the mouths of working people because of hip-hop, and then I read it on the page outside of the hip-hop quotables from The Source, in this text, and that really made poetry, for me, something else, and something to aspire to."

“I'm first and foremost a poet," he continues. "I love the poem. In some ways, we're in the best time to teach poetry because you can point to whoever, Lil Yachty or Chance or Noname or Jamila Woods and have young people believe and understand that poetry and this kind of expression is not only essential to the human condition, but it's also, as you say, cool. We are surrounded and immersed in a culture of poet geniuses. Hip-hop really has made poet kings and queens in that regards. The ability to hear language in new and interesting ways. Chance can influence and shake the governor of Illinois because of his ability to put words together.”

I mention rapper/English teacher Defcee, who assigns homework to his high school students to listen to tracks by MF Doom, A Tribe Called Quest, Kendrick Lamar.

“First of all, you'd be a fool to say MF Doom isn't one of the finest poets of the generation. We're now in an era where incredibly intelligent people can begin to challenge the ivory tower about what is and what isn't literature. Defcee teaches at Oak Park and River Forest High School. And he also teaches at YCA. He teaches our Emcee Wreckshop program. He's bent on really influencing this new generation of very talented, bar-heavy poet MCs.”

We talk quickly about BreakBeat Poets through YCA. “I'm interested in more anthologies," Coval begins. "Breakbeat Poets now has its own imprint on Haymarket Books. The next Breakbeat book will be a book entitled Black Girl Magic and it's edited by Mahogany Brown and Jamila Woods and another woman from Los Angeles and it's all black women. The next in that series is an anthology edited by Fatimah Asghar who wrote Brown Girls and Safia Elhillo, a very fine poet who just came out with a book called The January Children. The book is called Halal if You Hear Me, and it's for Muslim women and queer Muslim voices in stories. This time next year," he adds, "Northwestern University Press is putting out an anthology that we did called The End of Chiraq and the Fight for the Future of Chicago.”

The list continues. Coval mentions another play with Idris Goodwin, he mentions a film, and he mentions more poems. "I'm writing," he smiles.

Being as how I first saw him at a Sofar Sounds event, and how he recently finished speaking in front of thousands at Louder Than a Bomb, I ask him how he approaches different venues/capacities.

“My biggest influence is probably KRSONE and he says 'From 20,000 to ten in housing.' It doesn't matter. What a privilege to be able to share your work with anyone, so whether it's the individual reader in a book/publication or an auditorium of 4,000, it is still the same humility and hope that you'll be seen, you'll be heard, you'll be understood. Hopefully you'll motivate others to investigate the world in a new and meaningful way.”

With so much on Coval's plate, I ask him if he is still able to write every day. “I try to remain disciplined," he says. "My whole life has been built around getting up at 7:23 every morning in order to do that work, so I try to keep that discipline, in part because it's the work, but also it really does make a difference in my state of being. Writing is also a ritual for me, at this point.”

As the interview continues, we stray away a bit from poetry and books and I ask him about the best sandwiches in Chicago (“Good question”) and he mentions Nini's Deli cuban sandwich with turkey, he mentions a Polish/Korean fusion restaurant in Bridgeport called Kimski, and he mentions how 'the best Middle Eastern food is up on Albany Park'.

We close out the interview and ask Coval if he has any advice for artists working on their craft.

“I'm really privileged to have worked with thousands of artists throughout the city, throughout the country, and I hope for all of them to find the love and the passion in what they're doing because no one is gonna ask you to get up and make art. It has to be an incredibly disciplined and self motivated process. Especially starting out. You need that in order to propel yourself forward. Artists are made, they're not born. I've been trash. It's painful and hilarious to look back at early poems that I thought were dope. Through discipline, through reading and writing and repeating that process, you get better and better. The more you put in, the better you'll be. Seek out other artists. In your discipline, but also across disciplines. And if you are around a crew of creative people, they don't need to be like-minded, but they can push you in your own creativity and they can give you some suggestions and some critical feedback. You don't just wanna be in a space where you're gonna remain static as an artist, so seek out a community. Ultimately, that will save your life.”

Photo: Evan Brown

"Any final words of wisdom or closing thoughts?" I ask.

“I'm excited for people to read the book. I hope I get to meet and hear a lot of people throughout the course of this year, so if anyone is interested in having me out to do a reading and a workshop, that will be my year this year, for the next 365 days. I'm gonna be out in the city trying to really listen to what is on people's minds. If it's a barber shop, a bookstore, a dive bar, or a school, I wanna come out and help to facilitate a conversation and hear what people can contribute to this notion of The People's History of Chicago.”

With the book having been released yesterday and with the exhibit beginning at Chicago Truborn gallery on April 15 (which will run for five weeks), Coval has his hands full for the remainder of the season. It will be a delight to follow his progress as he speaks throughout the city over the course of the next year. With that in mind, it's only right that I end this interview with my introduction to Coval from the Sofar Sounds show back in September. We were in someone's high rise apartment, with the setting Chicago skyline as the backdrop, and Coval read the final poem of his collection:

“Chicago Has My Heart”