I'm still trying to wrap my head around the death of author Denis Johnson, who passed away on May 24 in his home in California. He was 67 years old and left behind one hell of a literature legacy. Although he was perhaps best known for Jesus' Son, his 1992 collection of short stories (which was later adapted into a film featuring a young Jack Black), Johnson began publishing poems back in 1969 and continued releasing fiction until 2014, with his final novel The Laughing Monsters. With ten novels, five books of poetry, five plays, two screenplays, and a book of essays, it's safe to say Johnson was prolific if not precise and methodical. Multiple years would pass between releases, with every new piece being something totally different than before. Touching on everything from a 'who dun it' noir (Nobody Move) to a turn-of-the-century panhandle novella (Train Dreams) to a Spanglish post-apocalyptic surrealist piece (Fiskadoro), Johnson never disappointed.

It came as a shock to read of Johnson's passing, who suffered from liver cancer. While he wasn't necessarily young, he also wasn't necessarily old, and with the cancer news not being public information, the death took most of the literary world by surprise. Now that my favorite author has passed, I will continue reading his poetry, his short stories (apparently a collection is arriving next year known as The Largesse of the Sea Maiden), and I will finally finish Tree of Smoke, the 624 page Vietnam War mind rattler and the only Johnson book I have yet to complete.

As a mean of properly paying tribute to my favorite author, I felt it necessary to revitalize a feature story on Johnson that I pitched around to various publications last year. The feature revolves around the notion that many know Johnson as the author of Jesus' Son, or of the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction finalist Train Dreams, or of the National Book Award for Fiction winner Tree of Smoke. While all of those three books are not to be missed, the late author has a plethora of content touching on multiple genres and styles. I’ve gathered together a list of my five favorite works by Denis Johnson that might not particularly be on your radar. Rest easy, old friend.

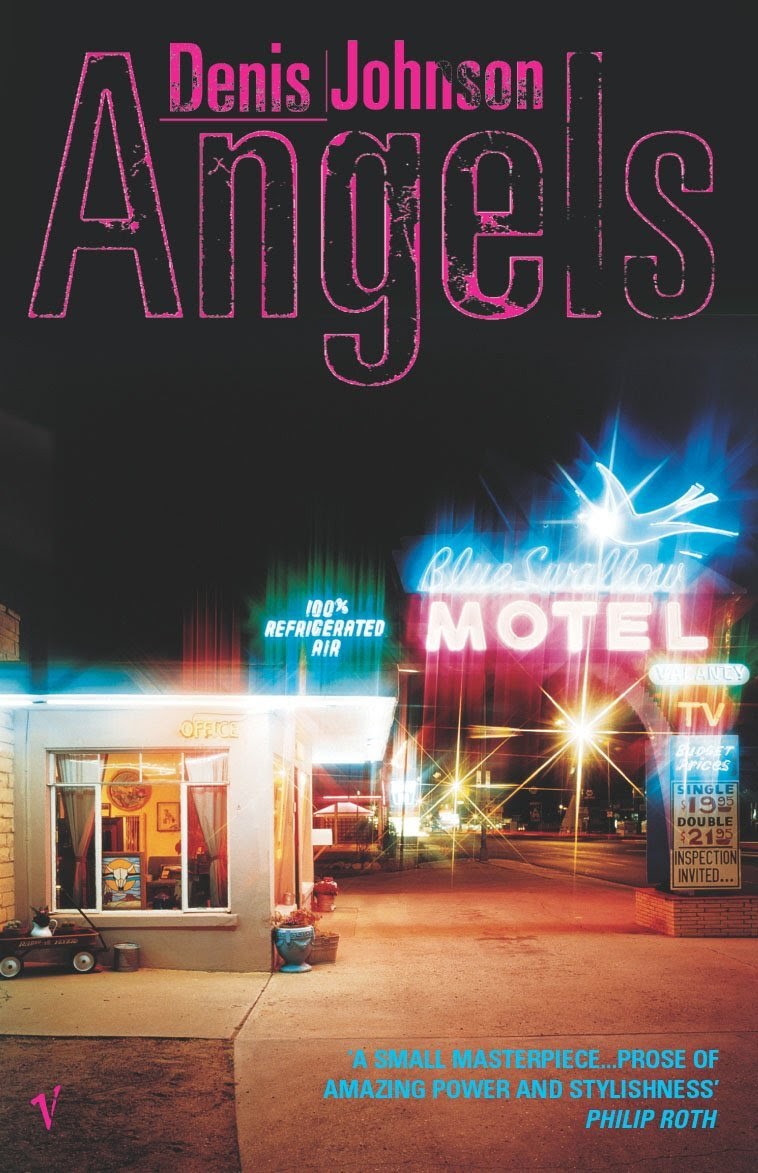

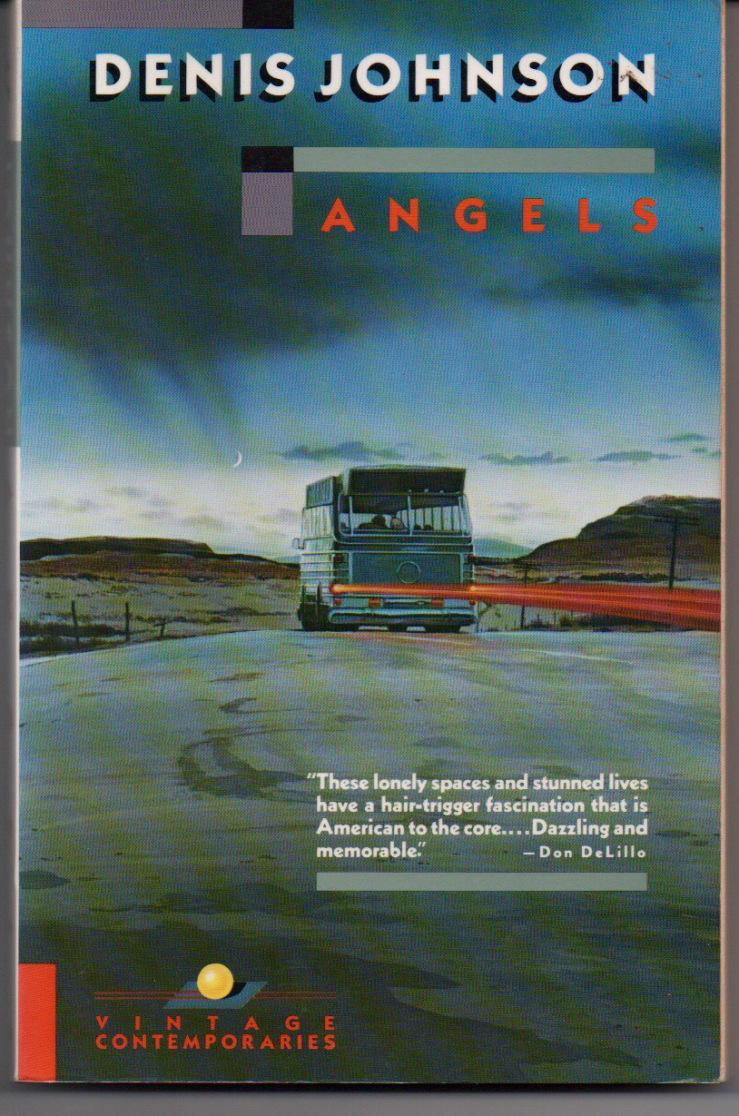

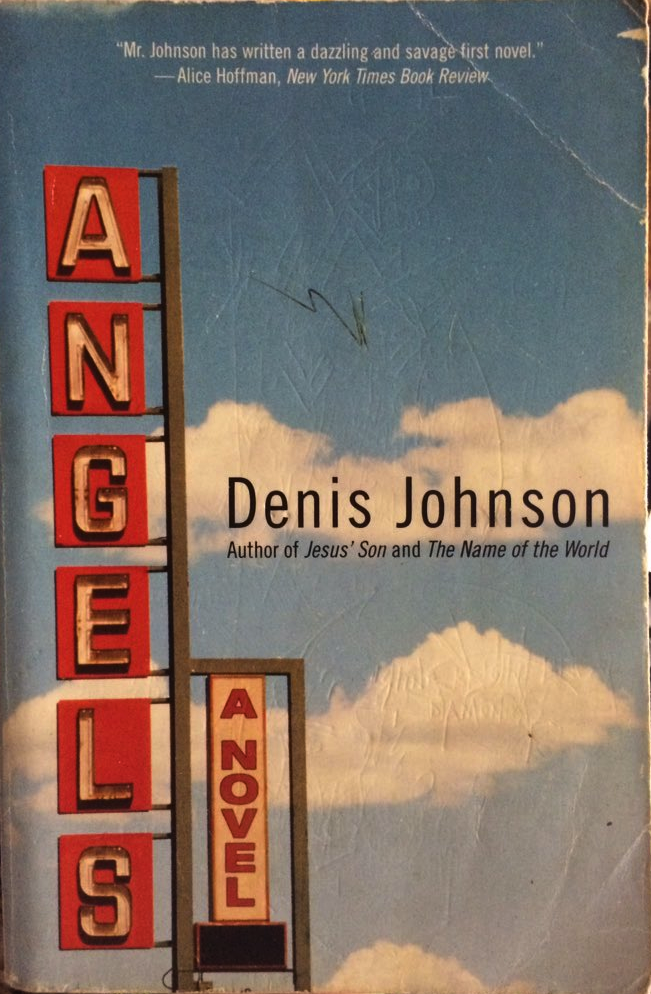

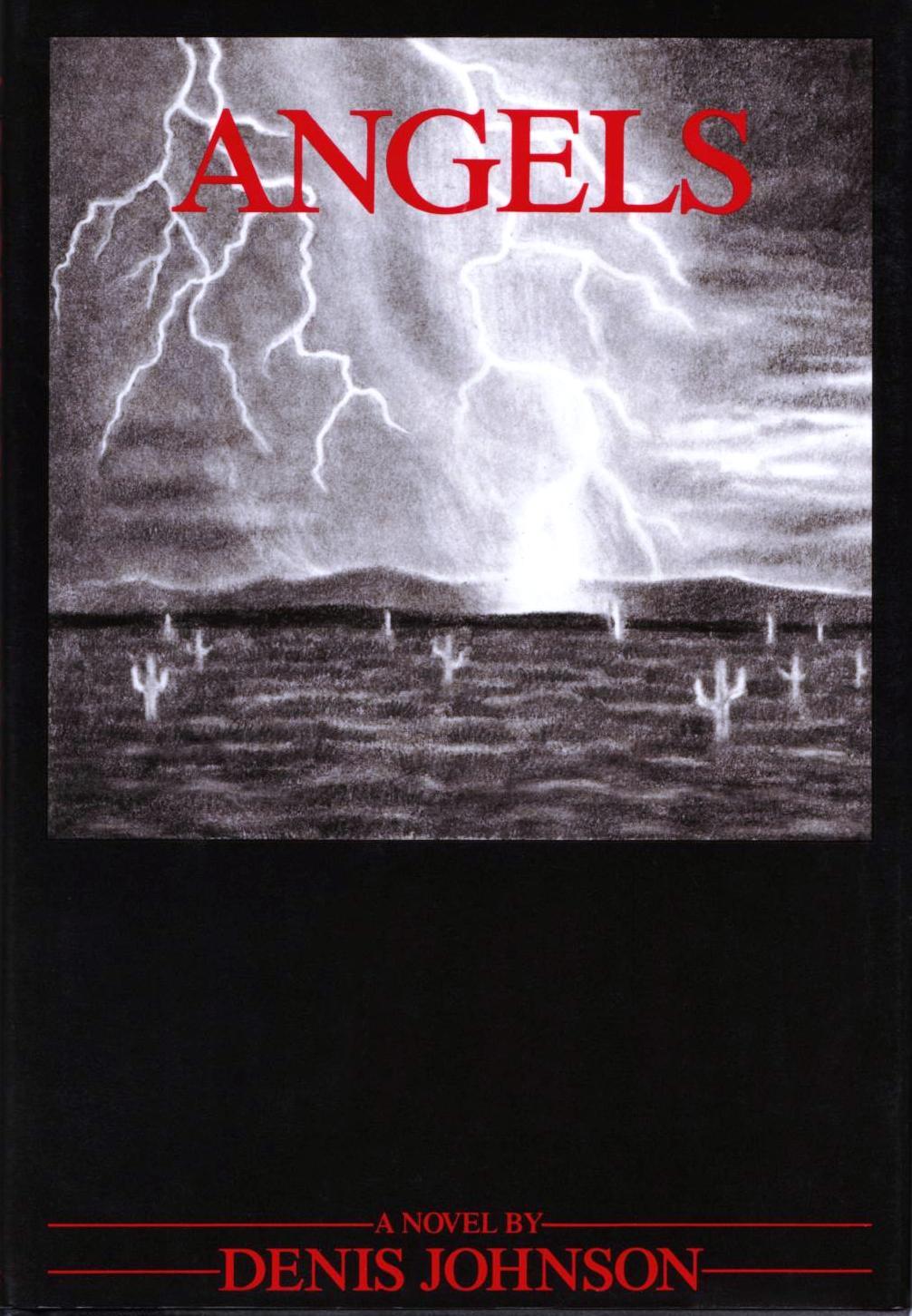

Angels (224 p.) (1983)

Johnson’s first novel is full of substance abuse, neglecting one's own kin, road trips in buses, death row, and, ultimately, redemption. The book was released when Johnson was 34 years old. If you enjoyed Jesus' Son, you will enjoy Angels. I found myself reading this debut book after David Foster Wallace included it in his 1999 Salon list of five “directly underappreciated American U.S. novels > 1960.”

One line (of many) that I underlined: “She noticed she was jiggling both her feet, clenching and unclenching her jaw until her head ached. Boy, if this ain't the very edge of it all, I just don't know, she thought.”

Fiskadoro (240 p.) (1985)

If you ask me my favorite Johnson book, I'll have three answers: Jesus’ Son (short stories), Train Dreams (novella), and Fiskadoro (novel). Set in a post-apocalyptic beach in the Floridian Keys, Fiskadoro is coated in Spanglish and hallucinatory imagery. I read it while I was on the beach of Ecuador, relating to the broken languages and the lazy days sitting by the sea. This might be Johnson’s most obscure book (and the one with the most mixed reviews), but I with each read, I find myself underlining multiple lines on every single page. I try to revisit it every year when the sun arrives in Chicago or once my toes touch an ocean.

One line (of many) that I underlined: “He woke up, and the moon was falling down on him. The moon had him looney tunes, a few monster things, a few ghosts, a few rrrrrrrrrr tiny psycho cyclers.”

The Incognito Lounge (80 p.) (1982)

Back in the mid-90s, Johnson released a poetry anthology called The Throne of the Third Heaven of the Nations Millennium General Assembly. The book was made up of four of Johnson’s previous poetry collections, as well as a few collected new poems. The book within the book that struck me the most was 1982’s The Incognito Lounge. I read each poem twice, thrice, four times over, internally gasping at the quality of each line, feeling the raw emotion that he was eliciting with his work of turning the mundane into something horrific yet magical.

One line (of many) that I underlined: “The moon's mouth is moving, and I am just leaning forward to listen...”

Seek: Reports from the Edge of America and Beyond (256 p.) (2001)

While Johnson’s voice certainly comes alive in his fiction (all forms of it), his singular work of non-fiction is as vibrant and surreal as the rest of his bibliography. It is here that he does mushrooms in the wilderness of Oregon, goes mining for gold in Alaska (with his wife, for their wedding bands), and covers Liberia's “civil war in hell.” He documents motorcycle enthusiasts hellbent on Jesus Christ. He compares Afghanistan to New Mexico to Kuwait. About 80 of the 250 page book is dedicated to the final passage in Liberia. Acting as its own book within a book, the lengthy essay throws you into the world that Johnson sees, both poetic and violent.

One line (of many) that I underlined: “A man with a guitar on his back and a loaded rocket launcher on his shoulder pointed his weapon every which way, shadowing a weeping young woman down the street.”

The Name of the World (144 p.) (2000)

Most of Johnson’s books are heavy-handed, sobering, and, yes, rather depressing, but it is The Name of the World that takes the metaphorical and undeserving cake. The book is told through the lens of a college professor, four years after his wife and child die in a car accident. He is understandably numb, going through the rounds, waiting for death to take him. This is a dark and deeply emotional read, despite only being 144 pages. With that being said, Johnson's style shimmers throughout the stream of consciousness prose, the odd characters who come and go through the narrator’s life, and the neverending poetics that help this novel shine.

One line (of many) that I underlined: “She was talking to her date, she didn't know the rest of us existed, the aging rest of us, the sane, or tame, rest of us. I felt very kindly toward her, glad of her presence, maybe because she was drunk and didn't care about herself."